Exploring Raqiya Volume 4

The penultimate volume of Masao Yajima & Boichi’s epic anarchic fantasy Raqiya: The New Book of Revelation revolves around violent conflict on both interpersonal and global scales. The divisions are distinct, intense, and harsh, and the book spends little time allowing the reader any respite.

The overt manifestation of protagonist Luna Hazuki’s devastating supernatural power triggers a new crusade throughout the western world. The ancient underground of Gnostics rises up in armed rebellion against the established Catholic religion and its secretive sect of Freemason political leaders. America, Europe, and the Orient suddenly errupt in open holy warfare using modern artiliary and ancient theocratic battle lines. At the same time, The Vatican debates its response within while without the very Vatican city is being reduced to rubble. Luna faces the leader of the Gnostic army and challenges him with ethical questions that neither of them can definitively answer, and the showdown between tragic friends Luna and Toshiya seems to reach its bloody climax.

Raqiya volume 4 reaches the largest scope of its narrative thus far with fairly praiseworthy effort. The book depicts a global crusade, but much of the illustration is limited to Japan and Italy. Readers are told more than shown the full scale of the new war, so readers comprehend but don’t necessarily “feel” the full extent of the war that rages around the perception of teenage girl Luna Hazuki. The large battle scenes are beautifully illustrated, but the book’s most impactful and memorable sequences are its smaller, more intimate conflicts: Cardinal Simacks’ argument with Pope Leo Lorentio, Luna’s philosophical debate with Chairman Nitobe, and the book’s climactic Mexican stand-off. Particularly Luna’s confrontation with Nitobe is powerful because it reveals a humanity previously unseen, but the debate is also a bit abstract and unfulfilling because the discussion has to occur in the absence of important relevant information. Since writer Masao Yajima is withholding the story’s most vital secrets for the final volume, the philosophical debate in volume 4 must occur, figuratively, with one arm tied behind its back.

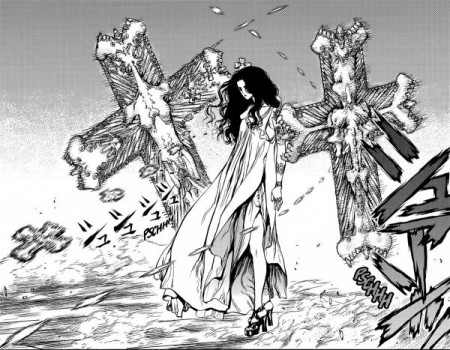

Boichi’s art, on the other hand, excels to its greatest height so far in volume 4. The book’s larger panorama allows for more epic depictions filled with ultra-realistic and ultra-detailed background art, mechanics, weapons, collateral damage, and also graphic content. Like previous volumes, scenes of graphic violence in this book are brief and infrequent, but when they do appear they’re intensely grotesque and visceral. The panty shots present in volume 3 resurface in volume 4 and escalate to partial nudity and one full page of graphic, non-sexual nudity.

One Peace Books’ localization of Yajima’s writing continues to read naturally. Sound effects are translated unobtrusively. However, unlike previous volume translations, book 4 contains at least four minor yet noticeable typos. On page 7 “My brother…” is clearly supposed to be “My brothers…” On page 9 an “it’s” should be “its.” On page 11 “Messalian” is incorrectly spelled “Messalien.” And a reference to the three wise men visiting Jesus, appearing on page 117, clearly should be “2000 years ago” rather than “200 years ago.”

Raqiya’s insistent reference to abstract concepts like “Anima Mundi” and “ichaeism” and religious movements including Catharism and Gnosticism may leave some readers confused, although a cameo appearance by “Ursula Leguin,” suggests that the writing its consciously satirical. Intense graphic violence also creates a natural barrier for select readers. From its outset Raqiya has been a manga for mature readers, perhaps no volume so far more so than this one. But after a measured start, the story is now rapidly expanding to the epic scale promised early in the narrative. Readers who have been tentative about the story can rest a bit easier knowing that as of volume 4, the writing and art delivers tremendously and effectively, if not exceptionally.