Ask John: Why are Doujinshi Allowed in Japan but Not in America?

Question:

If doujinshi in Japan is perfectly legal then why not allow it in America too? I see no reason why Viz and others can’t allow doujinshi of Bleach, Naruto, One Piece or Hunter x Hunter to be traded. Why do the Japanese get to live large and enjoy the good life with endless doujinshi for Japanse anime/manga while we have paranoia and rampant lawyers and fear over in the States?

Answer:

The Japanese term “doujinshi” refers to fan-created material, and thus has a very broad definition. Doujinshi can be print, music, video, software. Doujinshi can be entirely original material created and self-published, or can be parody, satire, or homage of characters and concepts created by someone else. Doujinshi can be created and published by amateur fans. Countless professional Japanese manga artists and animators also self-publish doujin comics privately. For example, Black Lagoon manga creator Rei Hiroe and Outlanders manga creator Johji Manabe publish adults-only parodies of their own works under the respective pen names “TEX-MEX” and “Studio Katsudon.” Character designer Nobuteru Yuuki has independently released self-published book collections of his concept art for assorted anime series.

The origins and nature of doujinshi in Japan and America are very different. And it’s particularly those differences that distinguish why doujinshi is accepted and even encouraged in Japan yet strictly discouraged overseas. Ironically, Japan has no “fair use” clause in its copyright law, meaning that Japanese law does not grant permission for individuals to refer to copyrighted works without advance permission even to honor, criticize, or parody. Simply making jokes that distinctly target a copyrighted character or concept is not “protected” free speech in Japan and can result in the joke-maker being sued for copyright infringement. Section 107 of US Code title 17, the “fair use” copyright clause, does allow Americans to refer to established, copyrighted works for the purpose of criticism and satire. In effect, American copyright law is more favorable to the creation and development of doujinshi than Japanese copyright law is, but tradition has an even greater influence than legality.

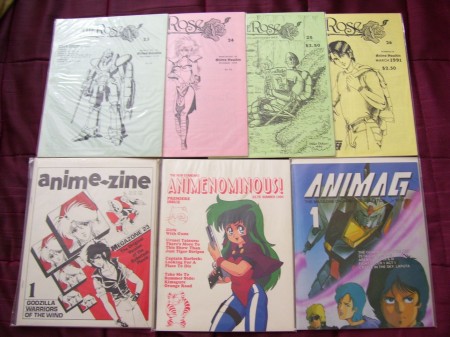

Prior to the internet, and prior to the modern era’s legal trigger-finger and corporate paranoia, Japanese fans began creating the own parody and homage comics in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The first Comic Market convention was held in 1975 and had over 30 doujinshi creator groups exhibiting work. By the late 1960s commercially published manga had existed in Japan for decades, and even the modern anime industry was nearly a decade established. So amateur fans that wanted to express their affection for popular manga and anime had plenty of opportunity to do so. In America, however, manga and anime weren’t remotely as commonplace and familiar. Similarly, America had no widely established tradition of self-published, independent comics. America’s independent comics boom, when individual American comic artists found the ability to print and circulate their own professional-quality comic books, didn’t occur until the early 1980s. Because anime fandom was limited and isolated, accessibility to anime extremely limited, and understanding of anime and manga limited in America during the 1970s and 1980s, the early American anime doujinshi publications were “fanzines,” rather than comics. Local anime fan clubs printed amateur magazines filled with fan art and, more prominently, articles that discussed anime and provided plot summaries and descriptions. While Japanese doujinshi were used to pay tribute to existing manga and anime, American doujinshi were used to educate and spread information about manga and anime.

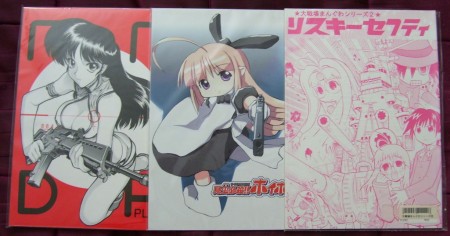

The Japanese grassroots doujinshi community served as, and continues today to serve as a breeding ground for tomorrow’s professional manga artists. Creating and selling amateur comics trains aspiring Japanese artists to draw and create characters and narratives that appeal to readers. Furthermore, Japanese ethics contribute to the continued prominence of doujinshi. The purpose of copyright protection is to prevent hard-working creators from having their creations stolen or misused. The established cultural sense of Japanese morality and intelligence largely prevents creators and consumers from confusing official “authorized” publications with unofficial, unauthorized doujinshi homages. In Japan doujinshi creations parallel, supplement, and even buoy the sales of official publications, just as the individuals that create doujinshi sometimes migrate into the professional industry. Today Japanese retail chain stores including Mandarake, Melon Books, Toranoana, and Lashinbang exist to sell unauthorized but widely tolerated doujinshi publications. Countless small Japanese printing companies thrive because fan artists pay them to print doujin comics. In effect, four the past 40 years the professional and corporate Japanese manga and anime creation industry has grown up as a sibling to the Japanese fan-created comic industry. The two markets are now inextricably intertwined and mutually supportive of each other.

Japanese consumers understand the symbiotic relationship between fan-created comics and professional publications. Japanese consumers immediately recognize the difference between self-published or independently published comics and mainstream commercially published works. Japanese creators are conscious of both independent and commercial publication; some artists work simultaneously in both fields. America is not the same way. Particularly with its long history of doujinshi and the uniformity of Japanese morality and etiquette, Japanese commercial publishers can’t, and largely don’t need to police Japanese fan artists for overstepping their roles and cannibalizing sales and profits from “authorized,” commercial publication. Since doujinshi isn’t already established in America, Japanese copyright owners have the opportunity to enforce their trademarks and restrict the creative control and image of their franchises to their own control.

For example, the Smile Precure character Yayoi Kise (Cure Peace) has a timid, almost childish personality. The Japanese fan community, particularly via the erotic doujinshi underground, has collectively exaggerated her personality, percieving her as easily sexually exploited and frequently associating her with urine due to the yellow color of her outfit. Likewise, the Japanese fan-created “Suzumiya Haruhi no Seitenkan” sub-genre gave birth to “Kyonko,” the female alternate version of Melancholy of Suzumiya Haruhi male character “Kyon.” While such fan exploitation and reinvisioning adds depth and diversity to the Japanese otaku community, it also dilutes the purity and strength of the singular “official” character descriptions and images that creators and publishers work so hard to establish and popularize. In America, Japanese publishers do have to ability to prevent the dilution and divestment of character and franchise images and reputations by strictly limiting who and how Japanese manga and anime franchises can be distributed in America. By limiting doujinshi and restricting the authorized distribution of anime to only select companies, Japanese copyright owners can ensure that every time an American consumer encounters a character or franchise, the consumer sees only a high quality product with professionally drawn art that reflects the character or concept exactly the way it’s officially supposed to be.

Furthermore, American distributors don’t want a rampant, unlimited amount of questionable quality depictions of anime circulating for sale in America because poor quality commerical merchandise begets suspicion about the quality of all American anime merchandise, not to mention cannibalizes the sales of authorized merchandise. Official domestic distributors like FUNimation, Sentai, and Great Eastern pay to be authorized ambassadors for particular franchises. These American companies pay for the right to introduce particular manga and anime franchises to American consumers. Thus these companies want to ensure that American consumers only see select anime in a positive spotlight that encourages affection, respect, and consumer sales that profit authorized, deserving distributors, manufacturers, and publishers. Fan art is one thing, but poor quality merchandise, or crude, obscene, or poor-quality comics sold at that same stores and conventions that sell the “real thing” cause consumers to spend money on the “wrong” goods and cause consumers to question the integrity and quality of the franchise. No one, including even the fan artists, wants that to happen.

According to the 2012 CIA World Factbook, 98.5% of the residents of Japan are ethnically Japanese. Doujinshi arose largely due to the uniformity of intention, good will, perception, and morality of Japanese people. America doesn’t have a near singular mindset and perception of fan-created homage works. Up until literally about five years ago, America didn’t even have a universal respect for comic books. Manga and anime doujinshi are a unique Japanese creation that are only supported, encouraged, understood, and appreciated in Japan. Japan is a uniquely fertile environment that allows for the spontaneous development and circulation of fan-created parody comics. America just doesn’t have the same multitude of circumstances, characteristics, and environment that allow for the positive growth of doujinshi culture.