Ask John: Is Black Representation in Anime Increasing?

Question:

Don’t know if you recently watched Netflix’s Yasuke (it could have been better) which was created by LeSean Thomas who also had notable projects in Legend of Korra, The Boondocks, Cannon Busters, Children of Ether. Based on popularity of recent animesque black characters in Afro Samurai, Boondocks, Black Dynamite, Seis Menos, also seeing teaser type trailers on Youtube that is trying to get crowdfunded like Urbance, Tephlon Funk, and Black Sands, do you see this as new type of genre? Mind you, it seems the creators of these series seems to take inspiration from Cowboy Bebop, Samurai Champloo or any creativity by Shinichiro Watanabe likes to use black inspired music (funk, jazz, hip hop) soundtracks in his shows.

Answer:

The creations of artists most frequently reflect the experiences and identity of the artist. That principle remains true regardless of era, ethnicity, and location. Black people appear infrequently within Japanese animation because black people are literally foreign to the vast majority of Japanese nationals. The population of Japan is exceptionally ethnically homogeneous. According to the World Bank, as of 2015 only 1.5% of Japan’s population was non-Japanese. Numerous estimates theorize that the current black population of Japan may be at most .03%. In effect, black people, residents or tourists, are infrequently seen in Japan, so naturally Japanese artists illustrate what they’re familiar with and what their audience will readily accept as believable.

Black characters within anime are infrequent and are typically supporting characters. Arguably anime’s first black character was Kurobee, the African native star of the 1973 television series Jungle Kurobee. However, in 1989 production studio TMS acknowledged that Kurobee could be perceived as an offensive racial stereotype and withdrew public availability of the Jungle Kurobee anime for 26 years. On a side note, in recent years Kurobee has developed a new sub-culture celebrity among Japanese otaku.

Into the early 1980s black characters continued to occasionally appear in anime in an unflattering light. Dragon Ball included several supporting black characters including Mr. Popo and Staff Officer Black. But Mr. Popo distinctly appears to be inspired by blackface entertainers, and Staff Officer Black’s name in Japanese is literally “Black Sanbo,” which sounds alarmingly similar to the racial stereotype “Black Sambo” (albeit, in Japanese language “sanbo” innocently means “staff employee”). Gainax’s 1985 OVA The Chocolate Panic Picture Show depicts African natives as curious yet ignorant primitives; however, the point of the anime was to encourage cultural sensitivity. At least as late 1990 the first Shin Karate Jigokuhen OVA depicted black people as practically modern day neanderthals; however, everything depicted within the Shin Karate Jigokuhen exploitation anime was a deliberate offensive exaggeration. Even Studio Ghibli’s 2010 film Ged Senki was accused of lightening the skin color of its characters compared to author Ursula K. Le Guin’s source novels.

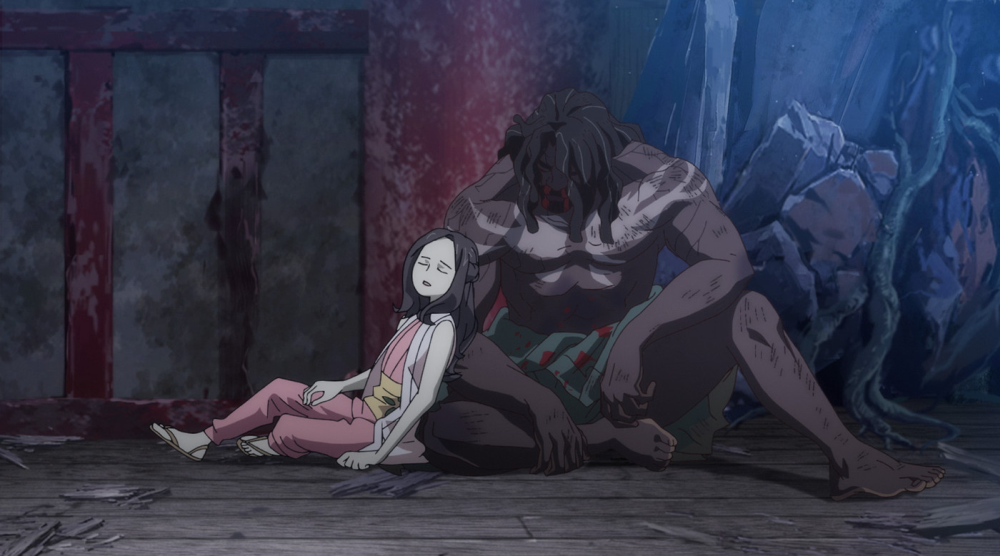

But starting in the early 1980s black anime characters also began to appear in a more even-handed spotlight, including Claudia Lasalle in Macross, Takenori Akagi in Slam Dunk, and Mukala in Samurai Troopers: Kikoutei Densetsu. Arguably, the first black protagonist of an anime is Nadia, the star of Gainax’s 1990 television series Nadia of the Mysterious Seas. Technically Nadia’s ethnic ancestry is alien, but she distinctly has dark skin and isn’t Middle Eastern or South American. Madhouse’s 2006 anime adaptation of Santa Inoue’s 1993 Tokyo Tribe manga could be considered the first anime to star black male characters, but the ethnic origins of the Tokyo Tribe characters has never been specified, to my awareness. Case in point, while the characters appear dark-skinned in the anime adaptation, they’re all portrayed by Japanese actors in the 2014 live-action film and 2017 stage play. The first definitively black male to headline an anime appeared in January 2007’s Afro Samurai, created by Japanese illustrator Takashi Okazaki. Subsequently black protagonists or co-leads appeared in 2008’s Michiko & Hatchin and 2019’s Cannon Busters and Carole & Tuesday.

African American pop culture began to seep into Japan in the 1970s. Doubtlessly films including 1974’s Gekitotsu! Satsujin Ken (“The Street Fighter”) and 1979’s Yomigaeru Kinro (“Resurrection of the Golden Wolf”) were influenced by the American blaxploitation film sub-genre. Hip-hop music was imported into Japan in the early 1980s by Japanese musicians including Hiroshi Fujiwara and Yellow Magic Orchestra. Scha Dara Parr’s 1994 “Konya Wa Boogie Back” became Japan’s first million-selling original rap song.

In the 1990s Japanese pop musicians including Amuro Namie significantly contributed to popularizing African American hip hop culture in Japan. Inspiration from African American music and fashion appears in anime including Tokyo Tribe 2, Parappa the Rapper, Samurai Champloo, Tenjho Tenge, Tonkatsu DJ Agetarou, B Street Rappers, Hypnosis Mic: Division Rap Battle, and D4DJ to name a few. But these productions, most notably among them Tokyo Tribe, emphasize Japan adopting hip-hop culture rather than anime depicting black characters.

American animator LeSean Thomas has had some limited success injecting prominent black characters into Japanese animation productions, but Thomas and his anime works are still an exception within Japan’s anime industry and seemingly not a harbinger of increased cultural diversity within anime. In spite of the contemporary global popularity and marketability of Japanese animation, the biggest market for anime remains overwhelmingly Japanese viewers who are overwhelmingly ethnically Japanese. And the animators who script, draw, color, and animate Japanese animation are overwhelmingly ethnically Asian. I don’t foresee any marked increase in black anime protagonists because there’s so little demand for such characters among the primary creators and audience for anime. Contemporary American culture is pervasively conscious of race, ethnic diversity, and equal representation. Japan has a very different social culture that doesn’t obsess over racial diversity and doesn’t contemplate a need for broad ethnic representation within its pop culture media.