Ask John: Should Creators Be Allowed to Alter Their Prior Works?

Question: Do you believe when an anime creator or mangaka releases a work to the public that it’s final? Should an artist be able to go back and change their work if they are unsatisfied with it? Should a corporation have the right if they legally own the property to change at their whim or should the original creator have the final say?

Answer:

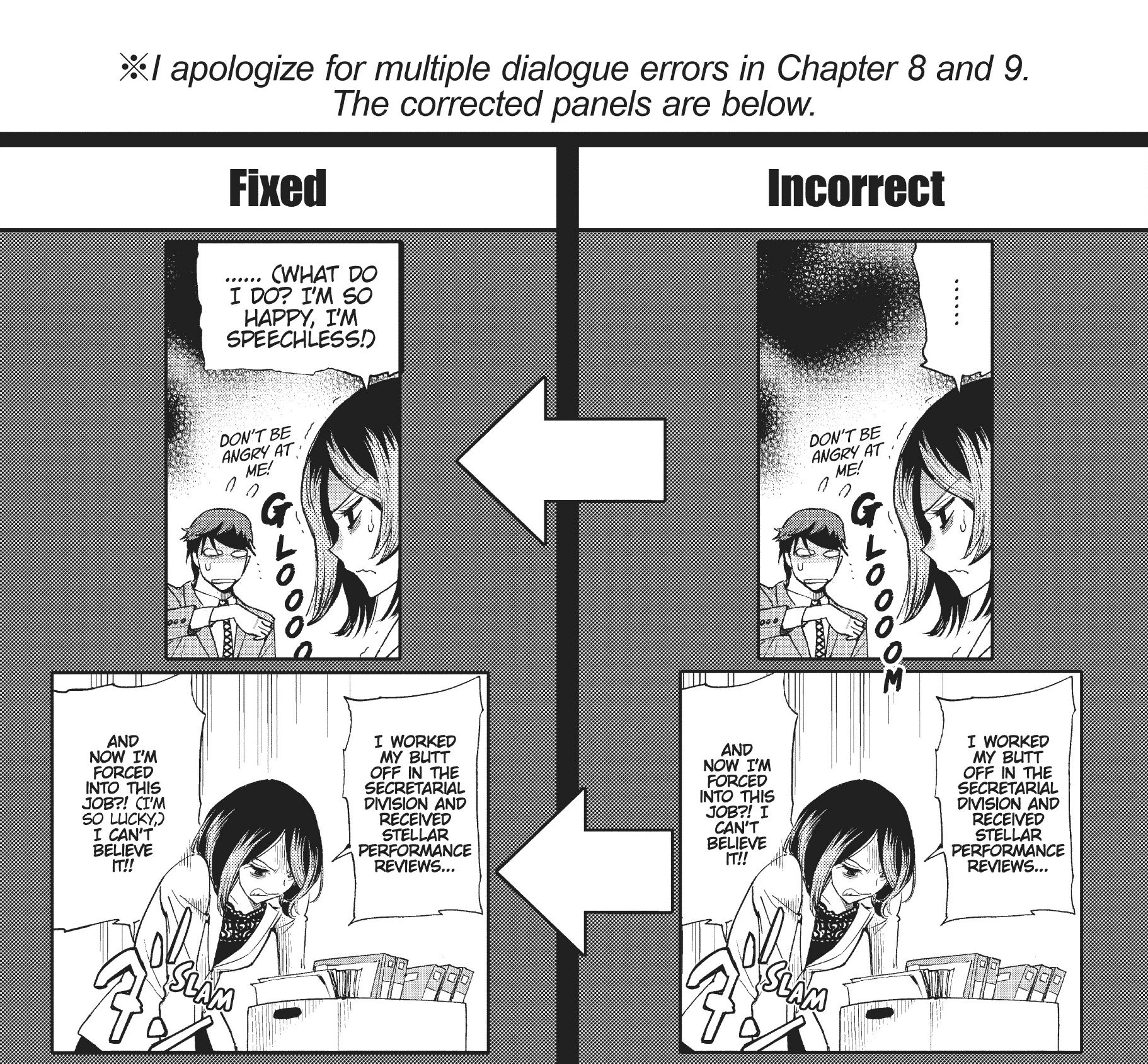

This question has two answers, and both are rather complicated. If the discussion is limited strictly to manga and anime, the answer is a bit clearer. At least in the modern era, the Japanese publishing industry and Japanese audiences have been receptive to the practice of revising literature post-release. Particularly because anime and manga are often created on tight schedules, Japanese audiences typically look favorably upon artists that clean up, correct, or revise their work after the fact. For example, the first collected volume of Yasuhiro Kano’s manga Kiruru Kill Me, published in English by Seven Seas Entertainment, includes addendum pages that show how one character’s dialogue in the original Shounen Jump+ online serialization was drastically rewritten for the print publication. The character Aijima’s personality was completely reversed from the original digital publication to the print publication.

A particularly famous example from anime derives from director Masahiko Ohta’s 2006 Yoake Mae yori Ruriiro na television series. In episode 3 a cabbage was illustrated as an unblemished green sphere. The cabbage was redrawn to look more realistic and identifiable as a vegetable for the series’ home video release. The “quality cabbage” became such a widely known joke, that nine years later director Tatsuya Yoshihara comically homaged the spherical cabbage in Monster Musume no Iru Nichijou episode 12.

To provide another egregious example, studio Arms fell so far behind on its production schedule for the 2014 Wizard Barristers: Benmashi Cecil television series that a dramatic scene from episode 11 was originally broadcast with most of its scene cuts missing. The animation was completed for the series’ home video release.

Typically, in the case of manga, the ultimate ownership and publication rights are the possession of the series’ creator. Frequently creators may wish to revise their own work, or creators will agree to requests for revision from their publisher. Instances in which a publisher alters a manga reprinting are rare. For example, in 2010 Gunnm (“Battle Angel”) manga author Yukito Kishiro publicly expressed frustration over publisher Shueisha demanding that he change three lines of dialogue that originally appeared years earlier in the first, third, and fourth collected volumes of his Gunnm manga.

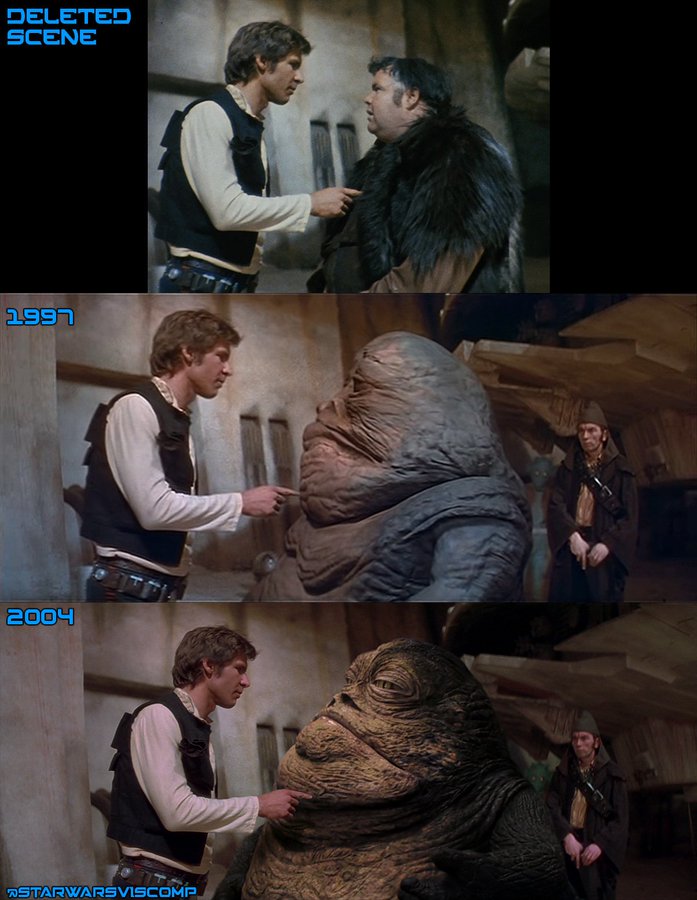

In western society, revision of published work is often a bit more tricky and complicated. Traditionally the literary field has loosely maintained the precept that a work should only be released publicly in its finalized form, and once finalized, a work remains in that form and status. Typically authors don’t continue to release repeated updates or revisions of the same novel. For better or worse, writers move on to the next work. However, revised editions of novels do exist. Revisions of films are much less common, yet one example is among the best-known examples to ever exist. Creator and director George Lucas explained his 1997 special editions of the original Star Wars films, “There were a lot of things in [A New Hope] I just wasn’t happy with and when the film came out everyone said, ‘Oh, looks great. You love it.’ I said, ‘Well, you know it’s only about 60 percent of what I wanted it to be’… This was an opportunity for me to really fix the film up and make it be what I wanted it to be. And get it to be at least 80 percent of what I’d hope it would be. And get rid of these little thorns that were stuck in there.”

Particularly since 1997 the commonplace fan sentiment has proposed that Lucas’ Star Wars films were immediately so popular and beloved that they transcended from being Lucas’ own artistic creation into an element of communal social culture. While George Lucas technically and legally owned the films and thus had a right to do with them as he chose, practically and philosophically the trilogy had become part of everyone’s lives and identities, so one individual changing the films for everyone, regardless of who that individual was, felt irresponsible and unjust. Time has salved some of the wounded feelings over the Star Wars Special Editions, and more recent developments from the Disney era of Star Wars output has further distracted attention away from resentment over Lucas revising his originally released films.

From a personal perspective, I’m highly conflicted. I composed my first notes and drafts for my own original concept Bloody Angel in 1994. I continued revising and rewriting the story until finally self-publishing the novel in 2017, twenty-three-and-a-half years after I started writing it. And for the past five years since releasing Bloody Angel, I’ve wondered nearly every day whether I should have written the novel with more accessible prose. I naturally speak and write in long sentences. I composed my novel to specifically have the audible rhythm I wanted. I chose the words that described exactly what I wanted to express. But would the book be more successful if it were easier to read? Would more readers actually read it if I’d written it with shorter sentences? To this day I’m still conflicted over whether I should respect literary tradition and my own original intentions by leaving the novel alone or whether I should re-write it in prose that’s more digestible.

Since I’ve consciously driven this analysis into concluding personal reflection, I’ll indulge just a bit further to selfishly mention that any reader curious about my anime-inspired fiction novel Bloody Angel may request a free digital copy from me by emailing: oppligerfj at Gmail. Securing readers has always been one of the most challenging aspects of composition, so I’d be tremendously happy to receive reader critique of my novel, both positive and negative.