Ask John: What do Americans Think of Anime Now?

Question:

Has America as a whole really moved passed the mid to late 90’s notion that “Anime is nothing but Magical Girls, Giant Robots and Porn,” and if so how far past that idea have we moved?

Answer:

During the past ten years, the mainstream American perception of anime has evolved into something quite similar to the mainstream Japanese perception of anime; however, while that evolution is desirable, it doesn’t reach the pinnacle that countless American otaku have hoped for. Particularly due to the intentional and practical efforts of early 90’s American anime distributors including Manga Entertainment, Streamline Pictures, and Central Park Media, anime became synonymous with exploitive, prurient cult cartoons in the minds of average Americans. In the early era of American anime distribution, a concentration on licensing, distributing, and promoting anime including “Robotech,” Angel Cop, Violence Jack, Vampire Hunter D, Urotsukidoji, and Akira, created a perception that anime was typified by giant robots, graphic violence, and gratuitous sexuality. Since mainstream America already presumed that animation was already a niche market, anime quickly earned a reputation for being an underground medium exclusively for lacivious, adolescent-minded cult fans who soaked up the colorful, fantastic images and chaotic, alien narratives. During those early days of the American anime invasion, anime that could dispel the myths or prove contrary to stereotype – family friendly anime and films like Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaa of the Valley of Wind – were only released in America in dubbed, edited versions that had no distinguishing connection to anime or Japan.

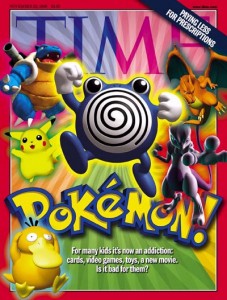

After nearly ten years of aggressive American distribution, the early 2000s finally began to see mainstream American perception of anime soften and expand. Time Magazine putting Pokemon on its front cover, Warner Bros. distributing Digimon theatrically, Disney acquiring distribution rights to the Studio Ghibli catalog, and the success of The Matrix – and the little known variety of cinema known as “anime” that had inspired the Wachowski Brothers – contributed to mainstream American recognition that anime, although foreign, was mainstream entertainment and not the unsavory, underground medium that Americans had unconsciously presumed that it was. As American parents came to be aware of anime through their children’s fascination with Pokemon and Dragon Ball, mainstream American film critics increasingly used the term “anime” without needing to explain what it meant, and American distributors largely stopped propagating the idea that anime was characterized by sex and violence in order to appeal to a broader audience instead of a niche, cult audience, anime briefly became “Japanese animation” before evolving into an umbrella term for brightly colored, highly stylized animation starring characters with big, round eyes, before starting to fall into simple obscurity.

Anime is no longer perceived as a distasteful, exploitive perversion of a medium for children’s entertainment. Much like mainstream Japanese, Americans now stereotype anime as a largely harmless, distinctively stylized school of animation. For contemporary Americans, anime is no longer Japanese robots and shower scenes; anime is any stylized animation targeted at families and harmlessly stunted viewers that insist on obsessing over cartoons in place of conventional, responsible live-action film. The perception is largely identical to the Japanese mainstream attitude toward anime. With infrequent exceptions like Hayao Miyazaki films, anime is a harmless distraction. It’s an “also exists” category of cinema similar to but not the same as foreign film or exercise videos – something for a small minority of enthusiasts to appreciate but not something which average, ordinary viewers need to pay much attention to.

In a bit of an ironic improvement, in twenty years the average American perception of anime has changed from negative and slightly offended to passively tolerant and dismissive. For years, hardcore American anime fans have dreamed of a time when ordinary Americans would perceive and respect anime as foreign art film, a medium that’s uniquely creative, intelligent, provocative, and beautiful. We’ve hoped for a time when anime would be respected, not merely recognized or even disparaged. However, that’s probably a dreamer’s aspiration. Anime has never been regarded with such high estimation in its native country, and while that fact doesn’t preclude the possibility of such respect developing in America, the present day disregard for anime in America suggests that the American perception of anime isn’t likely to degrade nor evolve in the foreseeable future. Mainstream America no longer looks at anime with suspicion and mild distaste. But these days mainstream America largely doesn’t look at anime at all.

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

I couldn’t care less about the general American population considering anime an art. I would just like the American population to accept and acknowledge it is more than kids entertainment to be dismissed and ignored. Just understand it is more than that and a single set of stereotypes will never come close to describing a single genre in anime, let alone the entire world of it.

American does have to respect it, watch it, understand it, or like it. They just have to accept it is more than a few words can describe and as diverse as American Cinema.

Speaking from my experience here in Germany, it was years ago that someone told me anime is only “Japanese cartoon porn”. However, most people associate anime with superficial impression frrom what they have seen on TV (like Pokémon or Studio Ghibli anime). John is right with the description that anime is “something for a small minority of enthusiasts to appreciate but not something which average, ordinary viewers need to pay much attention to.”

But now we have other kind of problems to face: How often do you hear in the web that anime is too emo or only commercial moe stuff ? Someone in real life even told me that he believed that the whole anime scene descended from the emo scene. -__- Can you believe that ?

You know, what’s funny is, when there was still a “debate” about Paprika influencing Inception [BTW, Nolan said it didn’t.], some douche on a different board tried to argue that Inception was the better movie morally, because there was no attempted rape scene. [Though I viewed it more as assault.] Then he tried to back-pedal when I brought up Carrie Anne Moss being smacked around in Memento.

Actually, GATS, I was led to an article around the time Inception was released that said Nolan was in fact inspired by Paprika in some part.

“Working with Tokyo’s Madhouse animation studio, Kon’s filmography included the kaleidoscopic dream-noir Paprika, a film Christopher Nolan has cited as a key influence for Inception.”

That’s from Empire Magazine.

Also, what does Memento have to do with a discussion about Inception and Paprika? Were you comparing Parika and Inception, or Memento and Inception?

Yotaru: Yes, and Empire based it off that fraudulent Excessif thing like everyone else. Nolan said in person he hadn’t seen it, and was only aware of it. As for Memento, my point was that it was from the same filmmaker as Inception, and also showed content which was not necessarily any more palatable than Kon, but somehow Nolan got a free pass, because one of his other movies was more “PG-13” than one of Kon’s movies.