Ask John: What Makes Certain Anime Evergreen?

Question:

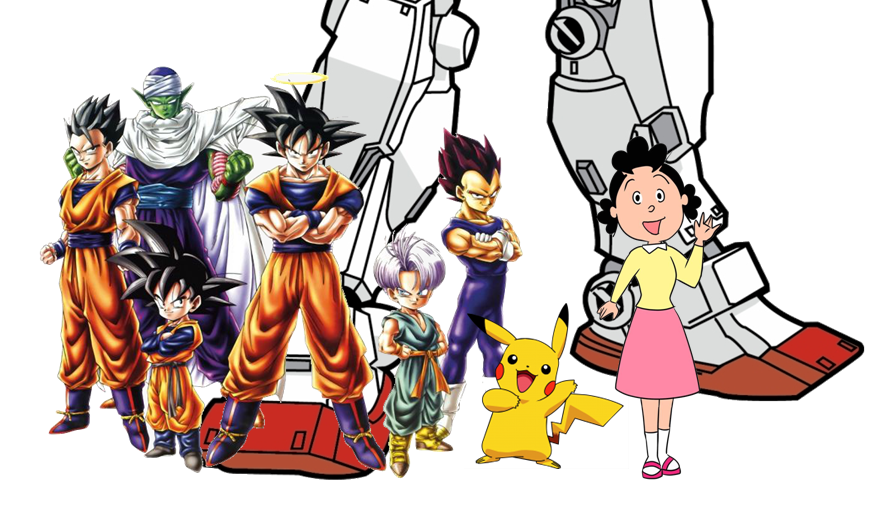

In your opinion, how is it that certain ideas in anime can last generations without becoming stale while others fall by the wayside? What separates something like Mobile Suit Gundam, Golgo XIII, Dragonball, Sazae-san, Doraemon, Lupin the Third, Pocket Monsters, etc, from not only other titles in their genres but last indefinitely? Is it because the ideas are malleable? Is it because of their heavy profitability in merchandising? Or am I missing something overall?

Answer:

As is the case with all ethnic cultures, certain stories resonate with a timeless significance because they reference the historical and mythological self-identify of their audience. For example, the United States was founded by colonialism and manifest destiny. America wasn’t founded on a spirit of religious faith, hunting and gathering, or collective security but rather by a sense of adventure, opportunity, and entitlement. Thus the imagery of the cowboy and the gunslinger are ingrained into the American self-identity, and now even artifacts of pop culture including Call of Duty and John Wick resonate with Americans despite not literally featuring cowboys. Yet these franchises still channel the independent gunslinger motif. So the exact same principle underlies the evergreen popularity of certain manga and anime franchises in Japan.

To address the specific examples named, titles including Dragon Ball, Golgo 13, and Lupin III tap into the Japanese mythology and tradition of bushido. Akira Toriyama’s Dragon Ball is a fundamentally a hybridization of the 16th century Chinese fable Journey to the West and the spirit of the romanticized samurai era, which was at its height around the same time. The Z warriors, Duke Togo, and Arsene Lupin III are men who strive for martial perfection. They seek to be perfect soldiers in their self-selected wars. And part of their sense of warrior pride is their code of honor. The Z warriors defend the weak, never bully a weakened or defeated opponent, and always seek victory through their own abilities. Golgo 13 works under a strict set of personal rules. Lupin always announces his thefts in advance, in part, to give his opponents a fighting chance against him. These warriors don’t carry swords (apart from Trunks) or wear hakama, yet they still exhibit the same mental fortitude and dignity that Japanese people respect and revere.

A modern parallel explains the perpetual popularity of franchises including Doraemon, Gundam, and Evangelion. Mechanical technological innovation literally invaded Japan when Commodore Matthew Perry landed in Satsuma in 1852. In the modern era, the Japanese psyche was permanently scarred when American military technology, the atomic bomb, once again invaded Japan and forced the country into a new era. Since the restoration following WWII, Japan has embraced technology more than any other country on earth. Anime including Doraemon, Evangelion, and Gundam are fundamentally about Japanese children learning to adapt to and live with robotic technology. In Doraemon the robot is a supportive and guiding best friend. In Gundam the robot is a means to power and exerting one’s will. In Evangelion the robot is literally a parent, a means of self-expression, and a means of gaining parental approval. In America mechanical technology, from the firearm to the cell phone, has always been a tool to extend human capacity. In Japan mechanical technology has traditionally been intertwined with culture itself. Evangelion’s concept of the Human Instrumentality Project is also deeply entwined with Japanese psychology of alienation anxiety, but close examination of that aspect of Evangelion is limited strictly to itself and not representative of a larger relevance to other anime.

And in the same way that Americans accept The Simpsons as a reflection of fictionalized typical Americana, Japan sees family programs including Sazae-san, Crayon Shin-chan, and Pokemon in the same light. For five decades and counting, Sazae-san has served as the defining image of the stereotypical Japanese family. Sazae-san is comforting because it’s familiar, ultimately reinforcing the fundamental family values of its people. Pocket Monster taps into the same spiritual philosophy that Hayao Miyazaki’s Nausicaa, Totoro, and Spirited Away do: a childlike respect for nature. Pokemon creator Satoshi Tajiri avidly collected insects as a child. Countless modern anime depict characters catching beetles. Even Japan’s most urban environments still have a remarkable amount of green nature within. Pokemon represents the Japanese spirit of communing with nature, being a partner with nature – using nature and animals to human advantage but not desecrating or exploiting nature. In Nausicaa, Totoro, and Pokemon, children “catch” wild creatures yet respect them as equals, partners, or even elders. Once again, Pokemon depicts an idealized image of the cultural and moral identity that Japanese natives aspire to. So not only is it entertaining, it’s also reassuring and reinforcing of Japanese social and psychological values. Shigeru Mizuki’s Ge Ge Ge no Kitaro is similarly an iconic Japanese franchise because the story encourages and values the Japanese sense of family, and its emphasis on youkai isolate and respect the uniquely Japanese cultural identity of Japanese ghosts.

Certainly plenty of other anime tap into these psychological aspects of Japanese culture. But certain titles do so first or more accessibly to a larger number of viewers, thereby becoming iconic. It’s these titles that cross-over into the awareness of the nation’s populace and become part of the country’s self-identity. In the same way that Steamboat Willie whistling to himself while cheerily steering down a river epitomizes American freedom and self-determination, Son Goku and Duke Togo represent the Japanese spirit of honorable diligence and self-responsibility.