Ask John: What’s Japan’s Reaction to Asian Copies of Anime?

Question:

There have been numerous reports recently about the Chinese media copying -nearly panel for panel- Japanese anime series and passing them off as their own series. What do Japanese fans and the industry feel about this? And why are copyright laws so completely unenforced in China (which is now the 2nd/3rd largest economy on the planet, and doesn’t need to be cheap about stealing anime)? If an American company were to produce and rip off Naruto with a series “Nharuto” that looked 99% identical, then there’s no way they’d be able to get away with it without having their pants sued off.

Answer:

The answer to this question involves international politics and the character of nations as much, if not more, than anime, so I’m hesitant to express observations and potentially offensive opinionated statements when I’m not an exhaustively educated expert on international politics. However, because this is a serious question involving anime I’ll provide a cursory answer. Allow me to emphasize that this is my own, personal theory formed from speculation and second-hand knowledge gathered from multiple sources. It seems to me as though Japanese otaku view original Japanese artistic concepts being liberally usurped by Chinese (and other Asian) countries with a mix of frustration and backhanded pride. The Japanese government overlooks the situation in favor of larger concerns. And countries including China adhere to a characteristically Asian sense of practicality to an extent that overshadows amorphous moral precepts.

It has been Asian anime fans themselves, both Japanese and Chinese, that have first noticed and drawn attention to obvious Chinese copies of Japanese animation including Kou Dai Xi Yuu, Xin Ling Zhi Chuang, and Astro Plan. The Japanese otaku sentiment about these copies seems to be a mixture of outrage and self-satisfaction. Japanese fans have been upset to see unique Japanese concepts shamelessly stolen, and subsequent Chinese animated productions taking credit for imagery that they didn’t originally create. At the same time, Japanese otaku seem to feel a sense of satisfaction in the knowledge that original Japanese anime concepts are evidently worthy of being stolen and recycled. This pride further manifests in a sense of satisfaction that Japanese creativity leads and other countries copy and follow. While Japanese otaku aren’t pleased to see their native concepts appropriated by foreign artists, these same Japanese otaku seem to feel some smug satisfaction that their original Japanese versions remain superior to the foreign copies. I do believe that this Japanese sentiment is consists of a mix of possessive pride, nationalism, and cultural superiority. I’m not criticizing, though, as I think that natives of every country instinctively feel some national pride and cultural exclusivity.

Japanese otaku may perceive Asian theft of anime concepts as a significant and pressing concern, but otaku are, typically, just otaku. The Japanese manga and anime creators whose concepts are being stolen know that a degree of appropriation is inevitable and, more importantly, practically impossible to prevent. Japanese creators know that creative influence affects and twines around them. So they should be aware that creative influence and inspiration travels further than Japan’s borders. Moreover, Japanese artists have been known to raise objection when plagiarism occurs within Japan, between Japanese artists, but not when the plagiarism occurs externally. When Disney’s The Lion King was widely accused of copying Jungle Taitei, Tezuka Productions did little more than smile and gracefully acknowledge some similarities. When American comic book creator Nick Simmons was accused of copying Bleach, Japanese creator Tite Kubo refused to make accusatory remarks. Anime, after all, is just anime.

The Japanese government has much larger and more weighty concerns than enforcing the intellectual property rights of Japanese cartoonists. Japan is a small Asian nation dwarfed by the neighboring powerhouse China and, in some ways, beholden to America. Faced with a choice of causing international friction stemming from copied comics or cartoons or encouraging friendly and beneficial national economic and diplomatic connections, the former isn’t even a serious consideration for the Japanese government. China copying anime is certainly an issue of Japanese concern, but on a relative scale, it’s a minuscule issue compared to larger issues of global economics and national defense.

China seems to exhaustively exploit the typical Asian respect for practicality and efficiency. Methods of accomplishing goals faster and cheaper are ideal. To that end, it’s more practical to utilize useful ideas that already exist than develop new, original ones. In their defense, Chinese animators behind Xin Ling Zhi Chuang, the television series that bears striking similarities to Makoto Shinkai’s earlier feature film 5 Centimeters Per Second, have reportedly admitted that they didn’t want to copy other works, but had to in order to meet artificially imposed production and budget deadlines imposed by the Chinese government, which commissioned the production. In Chinese society, which is so focused on concrete, measurable, practical trade, an abstract concern like respect for the ownership of ideas is largely an impractical hindrance.

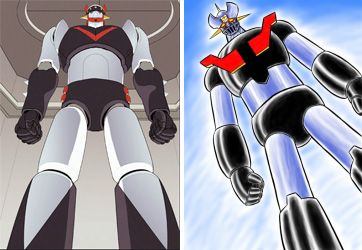

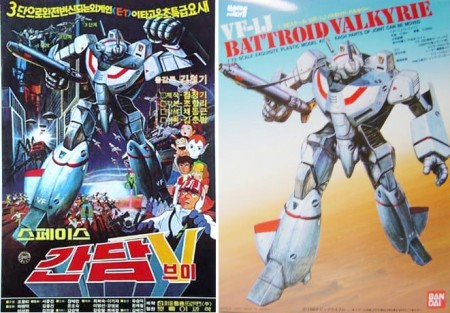

America is a little bit different because America doesn’t have such a strong and guiding insistence on results regardless of methods. The Lion King controversy has already proven that Japanese creators and copyright owners may be apt to passively accept instances of American appropriation of anime rather than attempt international lawsuit. But that situation isn’t likely to even occur because America’s creative industry maintains a self-imposed moral obligation to avoid plagiarism. Certainly exceptions occasionally slip through, and there’s a difference between shameless appropriation and homage or influence. But America hasn’t created any works like Korea’s Taekwon V and Space Gundam V, or China’s Astro Plan or Kou Dai Xi Yuu. Japanese copyright owners haven’t pressed for international legal restitution for instances of anime plagiarism in Asia because they know that such efforts are unlikely to succeed – not because the claim lacks merit, but rather because countries like China are unlikely to respect the claim. Japanese copyright owners likewise haven’t aggressively pursued intellectual property infringement cases in America – with the exception of claims involving physical goods like replica weapons, toys, and collectible cards – because they haven’t needed to do so.

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Don’t forget about cheap, counterfeit Haruhi Suzumiya on the Beijing Olympic brochures!