Ask John: Where Will Anime Go in America This Decade?

Question:

A lot has changed with anime in the USA in the past 10 years. What are your views of both the business and fandom side of anime in America going into 2010, as compared to 2000.

Answer:

In the fast moving anime industry, it’s really amazing how much has occurred and changed within only ten years. I’d love to say that the decade starting now will be equally or even more exciting, but at least on the American side, I’m not convinced that will be the case. Modern anime has existed in Japan for over 40 years, yet it only exploded as a commercial industry in America during the past 10, or 15 years to be generous. The American anime industry has also noticeably slowed and contracted recently, showing little sign of future explosive growth. So rather than a harbinger of future prosperity, the decade from 2000 to 2009 may have been the pinnacle of the American anime invasion. But that doesn’t mean, at all, that anime is doomed to extinction in America. Anime certainly has a future in America. I can’t predict for certain what that future will be, but I can hypothesize.

America’s otaku community has been active since the 1970s, but 2000, specifically, marked a new phase in American anime fandom with the advent of digital fansubbing. Up until 1999 Japanese anime typically took years down to as little as weeks to reach American viewers. Broadband internet connections coming into wide use allowed the first digital fansubs to surface in 2000, suddenly bringing anime to America faster, more conveniently, and to a larger audience than any time in the past twenty years. Through the decade the delay time on anime reaching America dropped from years to mere minutes. Pokemon and Yu-Gi-Oh both exploded within the past decade, exponentially expanding the American consumer audience for anime. The DVD format rose to prominence in the early 2000s, generating an unprecedented collector mentality among consumers that certainly aided anime. A greater number of American translation companies and anime/manga distributors were active during the past decade than during any other time in history. Anime became significantly cheaper and easier to acquire in America as the decade unfurled. Hayao Miyazaki became a widely recognized figure in American pop culture and an anime film won a major Academy Award for the first time ever. Even the word “anime” matured from being one which required explanation to one which mainstream America used reflexively. A strong start to the past decade, however, gave way to a diminished end.

Within the past three or four years at least nine American anime & manga licensor/distribtors have ceased operations. Many of the distributors that are still active aren’t as active as they once were. The demand for commercial DVD has drastically declined and Blu-ray hasn’t taken up the slack. Digital distribution, once predicted to be the future boom, has certainly expanded, but has yet to prove profitable. In recent years only one new domestic anime distributor has joined the industry with an actual release. The prominence of bilingual anime releases has plummeted. But within the bad, there’s also good. FUNimation has usurped the throne of America’s most prominent anime licensor/distributor. Viz has quietly continued to solidify its American foundation while simultaneously expanding in ever intriguing directions. Crunchyroll has opened the door wide to American/Japanese distribution partnerships. Examination of the present state of anime in America makes predicting the future difficult, but I do have a few premonitions that I feel confident to state.

Although Japan’s manga industry is facing unprecedented, frightening trends including declining revenue and diminished readership, there’s still more published manga in Japan right now than the American market will ever support. Ebook readers, multi-purposes cel phones, and other mobile devices are growing in use and prominence in America every day, suggesting that an explosive era of digitally distributed English translated manga is still ahead of us. The resource – manga – exists. The means of distribution exists. The potential American consumer market exists and is expanding all the time. It’s likely only a matter of time until businessmen connect these dots. Digital anime distribution hasn’t turned profitable, yet an increasing number of Japanese content owners are doing it, possibly motivated by the recognition that greater exposure generates intangible benefits. We may see the same approach applied to manga in the coming decade.

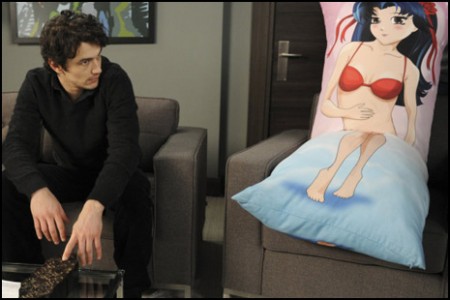

American and Japanese pop culture have long inspired and fed off one another. Otaku trends that have spawned in Japan, including phrases, maid cafés, character goods, and cosplay have migrated to America. The phenomena of moeacute; may be on its way as well. More specifically, the unique Japanese phenomena of “moéfication” may be on its way to America. Contemporary Japan turned everything from rice to mechanic’s tool boxes cute by adorning them with anime characters. The phenomena of pudgy cheeked, cute little characters has been present in anime for decades, but it was only identified as “moé” within the past ten years. America’s otaku community has initially largely recoiled at this new trend, but that attitude may be changing. Americans have long reviled cute anime about adorable little characters, except this year’s Hanamaru Yochien television series is suddenly the darling of America’s otaku community. Even more significant, actor James Franco on the January 14, 2010 episode of mainstream hit TV program 30 Rock appeared next to a dakimakura and said, “Do you know what moé relationships are? They’re when dysfunctional Japanese men fall in love innocently with fictional characters.” Moé has officially reached the awareness of mainstream American culture. It’s certainly possible for it to go no further, but I suspect that the moé march on America is only just beginning.

American/Japanese anime co-productions are nothing new, but in collaborations like The Animatrix, Batman: Gotham Knight, Halo Legends, and Dante’s Inferno we’re seeing a new sophistication and intermeshing of American and Japanese creativity. Even more relevant to my prediction, we’ve seen Peter Chung contribute character designs to Alexander Senki, and more recently American director Michael Arias direct a distinctly Japanese anime film. Furthermore, within the past decade we’ve seen an increasing number of anime productions created with the American market in mind, including D.I.C.E., Bakugan Battler Brawlers: New Vestroia, Afro Samurai, and Hellsing Ultimate. All of these circumstances lead toward one end which we haven’t seen yet: Japanese studios employing American directors to helm anime productions for the American market. Japan will always be the primary market for anime, and the majority of anime productions will always be produced for Japanese viewers. But when Japanese studios decide to occasionally craft anime in hopes of appealing to a foreign audience, it may make sense to seek input from advisers familiar with the intended audience. American directors supervising American created projects animated in Japan, like Halo Legends, isn’t the same as original Japanese projects bringing in foreign directors. Presently there’s no sign of this occurring in Japan, but the past ten years has taught us that there’s no telling what sort of revolutions lie in the future.

Add a Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.

No doubt it’s a little crazy to expect the kind of growth over the next ten years, which we witnessed from the past ten years. But if the business of licensing and distributing Japanese animation in North America is to continue on into 2020, I think it’ll have to grow to some substantial degree.

On the digital front alone, the greatest challenge (for FUNimation specifically), remains the desperate need to develop a fully scalable model for monetizing and thereby justifying the advance/exclusive distribution of content online. Lots of key terms there, and we all know this isn’t exclusive to the anime business, but if FUNimation and its industry partners hope to survive another ten years, a functioning model that takes specific advantage of the niche market, in tandem with a decent investment in competent yield management, is a must.

If this need isn’t addressed sooner rather than later, then FUNimation is simply contributing to yet another industry bubble (but when this one bursts… the results will be catastrophic).

BTW, the full ep is up @ http://www.nbc.com/30-rock/video/episodes/#vid=1193148 .

As for the Halo and Dante things, they look like fairly mediocre DTV affairs. I don’t just want cash-ins off popular properties. I want them to stand on their own, like The Animatrix and Gotham Knight. And Arias is a hack. I don’t want any gaijin attached to a project, just because of their connections. Nor do I want Japanese directors who have no business working on genre entertainment being given gigs, just because they’ve had a little bit of experience in live-action. [*cough* Resident Evil: Degeneration. *cough*] That’s how you get crap like DB: E. What I’m hoping will happen is the producers on the Japanese end will by-pass the American producers, directly seek input from domestic and foreign audiences about certain approaches to a genre of anime, and try to create products which have appeal on both sides of the Pacific. ‘Cus I sure as hell don’t just want a Hollywood-wannabe with Japanese names attached to it. It’s bad enough when the Europeans do that stuff.

I personally did not like the moe reference in 30 Rock because it put moe in a very negative light by directly equating it to the fetishization of dakimakura/love pillows. The term “moe” means feelings of protectiveness directed an an anime character. By contrast, dakimakura, men who want to marry anime characters, and other such practices are the sexualized extreme end of that definition. At its root, moe does not translate into romantic attachment. The creepy aspect of extreme moe practices are akin Islamic radicals: what they do makes the rest of the Muslim world look bad.

I appreciate when American pop culture references anime, but when they get things like this wrong, it just ruins public perception of it. For example, all of my friends who watch 30 Rock know I like anime, but if I told them I liked a “moe anime series,” they’d look at me a little funny until I explained exactly what moe really means and how the reference on 30 Rock is the creepy, fringe element.