Ask John: Which Anime Heavily Reference Shinto Mythology?

Question:

What are some anime that seriously delve into Japanese Shinto mythology?

Answer:

For modern Japanese citizens, Shinto is more tradition and social culture than a formal religion. A 2008 study conducted by the NHK television network determined that as of 2006 nearly 52% of Japanese citizens respected and practiced Shinto rituals such as praying at shrines and making offerings to deceased family but did not consider themselves “religious.” Illustrating this Japanese perception that Shinto is a heredity culture rather than an organized religion, the symbolism and conventions of Shinto theology are virtually omnipresent in anime; however, formal adaptations of Shinto mythology within anime are almost shockingly rare.

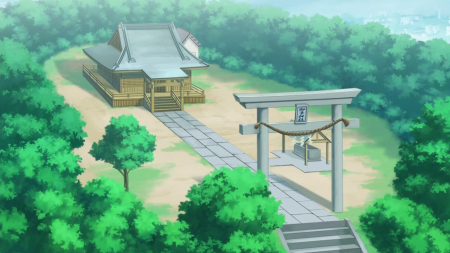

The torii gates and practically every temple seen in anime are Shinto temples. “Hatsumode,” the practice of visiting a shrine at the turn of a new year to pray for good luck, is seen in countless anime including Genshiken, Kimi ni Todoke, Lucky Star, K-On, Love Live!, and Uchoten Kazoku. The “miko” shrine maidens that appear in anime including Sailor Moon, Asagiri no Miko, Red Data Girl, and Yume Tsukai are representatives of Shinto. Anime including Kamichu!, Gingitsune, Inari Kon Kon Koi Iroha, Kannagi, Wagaya no Oinari-sama, Kamisama Hajimemashita, Natsume Yujincho, and Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi depict another level of Shinto principle by illustrating “kami,” the natural god-like spirits that inhabit all things.

However, anime that directly adapt specific Shinto parables or legends are seemingly rather rare. The two oldest known recorded documents in Japan are the Kojiki and the Nihongi, both histories of ancient Japan and the foundational tracts of Japan’s Shinto religion. Both documents begin with the mythological creation of the world, the descent of the gods, and the creation and development of humankind. Toei’s 1963 film Wanpaku Ouji no Orochi Taiji is based on the Kojiki‘s story of Kushinada-hime. Likewise, Production I.G’s 1994 television series Blue Seed, based on Yuzo Takada’s 1992 manga, is also inspired by the same myth. Nippon Animation’s 1994 shounen mecha anime Yamato Takeru is very loosely inspired by the Kushinada-hime legend. And the story arc that introduced Oolong in Akira Toriyama’s Dragon Ball is also inspired by the Kushinada-hime myth. The 1990 OVA series Ankoku Shinwa (“Dark Myth”) includes some very loose adapted references to Shinto creation mythology but can’t be considered any sort of legitimate adaptation of the Kojiki.

Studio Shaft’s 2013 television series Sasami-san@Ganbaranai, based on author Akira’s light novel series, is a parodical contemporary interpretation of Shinto mythology that stars Sasami Tsukuyomi, a girl ironically bearing the name of the Shinto moon goddess but possessing the power of Tsukuyomi’s sister, the Shinto sun goddess Amaterasu. Sasami’s companions are named after, and represent, artifacts from Shinto lore including the Sanshu no Jingi, the Japanese Imperial Regalia.

Despite the rich breadth of characters and stories within Shinto creation mythology, anime has traditionally rarely used them as a foundation for literal adaptation or inspiration. A parallel may be drawn with the way The Bible contains hundreds of separate stories, yet only a handful of them are routinely tapped as inspiration for American cinematic adaptation. With Shinto lore in Japan and Christian dogma in America, much more frequently it’s only the commonly recognized symbolism and the widely recognized rituals of common religion that get illustrated and employed in popular cinema.