Ask John: Who are the Most influential Manga & Anime Creators in History?

Question:

Along with Osamu Tezuka, who are the most influential creators in manga and anime? I’d imagine Go Nagai for his work with super robots, Cutie Honey and Devilman, Shotaro Ishinomori for Cyborg 009 and his contributions to Super Sentai, and Rumiko Takahashi for her many works and contributions to the harem genre are among them. But there are, of course, many more creators and I would like to know more about them and their contributions. I don’t want to limit this question to a specific number of creators because I want to know about as many of them as possible. Even if their careers are not as prolific as others, their contributions might still be felt to this day.

Answer:

Perhaps obviously, addressing this question is akin to summarizing the entire history of modern anime. Certainly a thorough examination of the most influential creators in the world of manga could fill multiple textbooks. For example, one worth considering is Masanao Amano’s hefty reference book Manga Design, but that book excludes animators.

My aim is to merely provide a reference for further research. Regrettably, I don’t have the discipline necessary to compose a substantial book-length examination of the influential figures in the evolution of modern anime. So instead I’ll cite some names and brief attributions, in no particular order.

The question mentions Shotaro Ishinomori, whom I frequently contextualize beside Mitsuteru Yokoyama. While Ishinomori arguably invented the “sentai” hero when he created Kamen Rider, Mitsuteru Yokoyama is responsible for both the earliest giant robot and magical girl anime, having created both Tetsujin 28-gou and Mahoutsukai Sally. Tetsujin 28-gou gave modern audiences the concept of the heroic giant robot that battles to defend justice. Mahoutsukai Sally introduced the concept of the girl from a magical world who came to live on Earth, a concept still used in today’s anime like Gabriel Dropout.

While Kamen Rider, the genesis of the sentai hero, was created by Shotaro Ishinomori in 1971, it was Speed Racer creator Tatsuo Yoshida who revolutionized the concept the following year when he introduced Science Ninja Team Gatchaman, thereby introducing the sentai hero team. Granted, Ishinomori did actually introduce Rainbow Sentai Robin in 1963, but that series is more accurately characterized as a single hero supported by his six robots rather than a team of equal heroes. Gatchaman introduced the five-member hero team that has appeared in countless live-action sentai hero series along with anime including Go Lion, Bubblegum Crisis, Dragon Ball, St. Seiya, Samurai Troopers, Sailor Moon, and Pretty Cure.

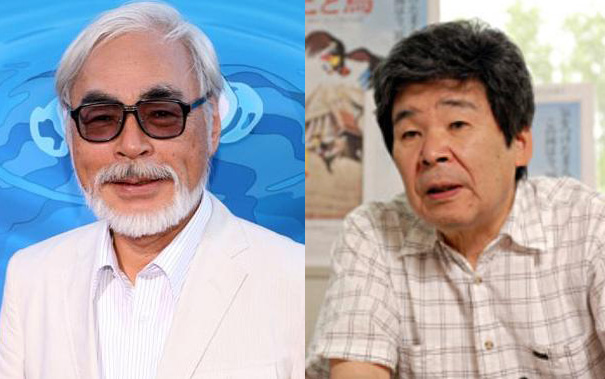

Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata are towering figures in the anime industry. Apart from creating many of history’s most successful and beloved anime, the influence of their animation styles, characterization, and storytelling can be seen in the works of younger directors including Mamoru Hosoda, Makoto Shinkai, Goro Miyazaki, Hiroyuki Okiura, Hiromasa Yonebayashi, and in Yoshitaka Fujimoto’s very Miyazaki-esque 1993 Minky Momo: Bridge of Dreams OVA and Takayuki Hirao’s 2013 film Magical Sisters Yoyo & Nene.

Yoshiyuki Tomino and Ryosuke Takahashi are both equally influential figures that followed in the footsteps of Go Nagai, who himself refined and evolved concepts introduced by Mitsuteru Yokoyama. While Go Nagai brought a grim grittiness to giant robots, and placed a human pilot inside a giant robot for the first time, Yoshiyuki Tomino and Ryosuke Takahashi, in creating shows including Mobile Suit Gundam, Heavy Metal L-Gaim, Space Runaway Ideon, Armored Trooper Votoms, and Blue Comet SPT Layzner, expanded the world of perspective of anime beyond Go Nagai’s “super robots” with the concept of “real robots.”

Just prior to and concurrent with Tomino & Takahashi’s contributions, Leiji Matsumoto’s shared sci-fi universe of Millennium Queen, Galaxy Express 999, and Captain Harlock, and separately Space Battleship Yamato popularized the anime space opera, without which viewers wouldn’t have seen later series such as Superdimensional Fortress Macross, Legend of the Galactic Heroes, Outlaw Star, and Moretsu Space Pirates.

Not primarily a manga-ka, Shouji Kawamori planted his landmark in the history of anime just after Yoshiyuki Tomino did by creating Superdimensional Fortress Macross. Tomino technically created, or co-created the anime transforming robot to anime when he directed 1975’s Brave Reideen television series, but it was Shouji Kawamori’s first episode of Macross in 1982 that really introduced the full possibility of transforming robots. Furthermore, while earlier anime including Sasurai no Taiyo, Sue Cat, and the Pink Lady biographical anime TV special introduced the concept of idol singers to anime, it’s arguably Kawamori’s Lynn Minmei that established the iconography of modern pop idol singers that led to anime including Idol Defense Force Hummingbirds, Creamy Mami, Chou Kuse ni Nariso, and today’s Locodol , Idolm@ster, Wake Up Girls, and Love Live.

Average American otaku aren’t familiar with Ikki Kajiwara and don’t realize the tremendous contribution he made to the advancement of anime. Kajiwara profoundly influenced that manga community and is virtually single-handedly responsible for the massive sports anime genre because he created Ashita no Joe, Kyojin no Hoshi, and Tiger Mask, not to mention Karate Baka Ichidai, Akakichi no Eleven, Karate Jigokuhen, Kick no Oni, Samurai Giants, and Yuuyake Banchou, all of which got anime adaptations. Ashita no Joe was the first boxing anime, which paved the way for later anime including Heavy, Slow Step, Ring ni Kakero, and Hajime no Ippo. Kyojin no Hoshi was the first baseball anime, which laid the groundwork for later shows including Captain, Dokaben, Touch, and Okiku Furikabutte. Tiger Mask was the first pro-wrestling anime, later followed by Kinnikuman?, Plawres Sanshiro, Wanna-Be’s, and Sekai de Ichiban Tsuyoku Naritai. Ikki Kajiwara introduced so many of the sports anime characterizations and narrative tropes that viewers now assume are typical of sports anime.

American otaku likewise may not be familiar with Kazuhiko Shimamoto because his influence is smaller yet very prominent. The concept of the transfer student who has to prove himself at his new school precedes Shimamoto’s 1983 satirical manga Honou no Tenkousei by many years, going back at least to 1970’s Bakuhatsu Goro. But Kazuhiko Shimamoto’s “Blazing Transfer Student” popularized the exaggerated, satirical concept of the hot-blooded, ever-optimistic young man who would always get back up, always give his best, always overcome his own limitations and his opponents. The influence of this sort of absurdist exaggeration reappears in Hideaki Anno’s Anime Tenchou, Kyosuke Usuta’s Sexy Commando Gaiden: Sugoiyo!! Masaru-san, Nami Sano’s Sakamoto desu ga?, and in characters such as Martian Successor Nadesico’s Gai Daigoji. Blazing Transfer Student was also a primary inspiration for director Hiroyuki Imaishi’s popular 2013 television series Kill la Kill.

Tetsuo Hara and Takao Saito both have one monumental creation apiece that have forever altered and influenced anime. Tetsuo Hara & Buronson co-created Fist of the North Star in 1983, predating Akira Toriyama’s Dragon Ball and Masami Kurumada’s St. Seiya. Particularly because he co-wrote and also drew Fist of the North Star, Hara must be credited with not only launching anime’s modern shounen martial arts subgenre but also introducing the visual design of intimidating muscular men that has now become a classic anime visual gag. Likewise, Takao Saito was not the originator of the “gekiga” manga style, but arguably his Golgo 13 manga contributed more to the popularization of the gekiga style than any other manga. And likewise, the visual design of a distinctly Japanese male face with sharply angular cheeks has become the de facto anime visual design for tough, adult Japanese men.

Kazuo Umezu is yet another monumental figure whom average American otaku may not be especially familiar with. Umezu’s 1972 Hyouryu Kyoushitsu (Drifting Classroom) horror manga is largely responsible for establishing the now iconic “Umezu reaction face” that’s a commonplace visual gag in anime. Furthermore, without Umezu’s classic 1976 manga Makoto-chan, which got an anime film adaptation in 1980, we might never have seen Yoshito Usui’s Crayon Shin-chan, which seems to draw a lot of inspiration from the earlier Makoto-chan series.

Gainax co-founder Hiroyuki Yamaga helped pave the way for directors including Katsuhiro Otomo and Satoshi Kon to create anime feature films with stunning, elaborate animation quality when he fought for the budget and support to create 1987’s Wings of Honneamise feature film. Certainly animators including Hayao Miyazaki & Isao Takahata had produced stunning animated films prior to ’87. But unlike directors including Miyazaki that had come up through the professional ranks and developed their skills and reputations by working with established studios like Toei, TMS, and Topcraft, Yamaga’s Wings of Honneamise was the most expensive anime feature ever made at the time, and it was crafted by a studio founded by college graduate friends who had never made a feature-length anime before. Hiroyuki Yamaga, Gainax, and Wings of Honneamise proved that upstart talented but amateur animators could break out with iconic masterpieces, as later directors including Katsuhiro Otomo did with Akira, Satoshi Kon did with Perfect Blue, and Makoto Shinkai did with Voices of a Distant Star.

Adult manga artists Fumio Nakajima and Toshio Maeda, and animator Tatsuya Shingyoji must be acknowledged for their impacts on the development of modern anime. The first ever erotic anime, excluding anime such as Sennin Buraku (1963) and Cleopatra (1970) that included nudity and sex but weren’t “ero-anime,” was the Lolita Anime six-episode adaptation of Fumio Nakajima’s manga animated by studio Wonder Kids. The second ever adult anime series was Cream Lemon, initially animated by studios A.P.P.P with assistance from studio Dr. Pochi. Tatsuya Shingyoji is widely credited as the character designer, storyboard artist, and animation director behind the first Cream Lemon OVA. Kadokawa’s 1985 reference book Bishoujo Anime Cream Lemon Original Video Collection also cites Shingyoji as the director for the first Cream Lemon episode. While there hasn’t been historically a lot of consistency or similarity within the adult anime sub-genre, it certainly needs to be acknowledged for being a prominent component of the development and expansion of anime as an art form. Toshio Maeda infamously created the “demon rape tentacle” as a circumvention of the Japanese government’s prohibition on the cinematic depiction of genitalia. The provocative groping tentacle has slithered out of adult anime and invaded mainstream anime.

Not to exclude ladies, Riyoko Ikeda’s 1972 manga Rose of Versailles contributed tremendously to the popularization and now commonplace association of Italian fashion and modern Japanese teenage girl romanticism. The countless “ojousama” characters in anime that wear frilly dresses and walk with a parasol owe thanks to the influence of Riyoko Ikeda.

Rumiko Takahashi also demands recognition not just for being a talented writer & artist but notably for inventing the “harem” anime concept with her 1978 Urusei Yatsura manga. Ataru Moroboshi was surrounded by a bevy of girls that he was interested in but who mostly weren’t interested in him, so one could argue that it’s actually Yuu Watase’s Fushigi Yuugi and Masaki Kajishima’s Tenchi Muyo, which both premiered in 1992, that truly introduced the definitive “harem” concept. But the core concept of one boy surrounded by many girls in a romantic comedy narrative was Rumiko Takashi’s creation.

Although Mitsuteru Yokoyama created the magical girl and Tatsuo Yoshida created the sentai hero team, Naoko Takeuchi is the creator who combined both concepts for the first time when she created Sailor Moon in 1991. Unquestionably, the success of the magical girl team lead to subsequent anime including Wedding Peach, Tokyo Mew Mew, Ojamajo Doremi, Pretty Cure, and Madoka Magica.

Gen Urobuchi is neither a manga-ka nor animator but rather a tremendously influential anime screenwriter. Urobuchi debuted in the anime industry in 2000, but it’s particularly his 2011 Puella Magi Madoka Magica that contributed to evolving the concept of the anime magical girl. Anime magical girls had dealt with death before. Osamu Tezuka’s Marvelous Melmo began with its protagonist having to deal with the death of her mother. In 1983’s Minky Momo episode 46 the fairy princess Momo dies in a traffic accident. (She’s later reincarnated as a newborn human child.) Hime-chan died in 1993’s Hime-chan no Ribbon episode 18. (She was resurrected.) Most of the Sailor Senshi die multiple times throughout Sailor Moon. But Madoka Magica introduced a grim, deconstructive re-examination of the foundational principles of the magical girl concept, leading to subsequent shows including Mahou Shoujo Ikusei Keikaku and the “WIXOSS” franchise.

Doubtlessly I’ve overlooked other significantly influential creators. Shigeru Mizuki and Akira Toriyama are among the most popular manga creators in history, but exactly how much their works influenced (distinct from inspired) subsequent creators is debatable. CLAMP is a landmark for the success of a female-exclusive manga creative group, but once again exactly how much CLAMP has influenced later creators isn’t as clear. Makoto Shinkai has unquestionably established himself as one of the most impressive individual principles in contemporary anime creation, and his visual style has appreciably influenced fellow animator and director Ushio Tazawa, whose 2008 Taisei Kensetsu: Shin Doha Kokusai Kuukou TV commercial is often mistakenly credited to Makoto Shinkai. But I’m not certain that Shinkai’s work has had a noticeable influence on other creators in the anime industry. Anime directors including Yoshiyaki Kawajiri, Akiyuki Shinbo, Akitarou Daichi, Shinji Aramaki, Yuuji Moriyama, Satoshi Kon, Kunihiko Ikuhara, Shinichi Watanabe, Shinichiro Watanabe, Mamoru Oshii, Mahiro Maeda, literally, just to name a few, have had tremendous success in Japan’s anime industry and have been highly influential on American fans. But their influence on fellow Japanese creators is uncertain. Likewise, manga creators including Masamune Shirow, Katsuhiro Otomo, Masashi Kishimoto, Eichiro Oda, Yoshihiro Togashi, Nobuhiro Watsuki, Tsugumi Ohba, Kentaro Miura, Kouta Hirano, and Yasuhiro Nightow have had tremendous influence on American manga readers, but I can’t say how much influence they’ve had on fellow Japanese creators.