Commendation for Kuma Miko

Creator Masume Yoshimoto’s breakout hit manga series Kuma Miko: Girl Meets Bear is a distinctly Japanese story steeped in Japanese culture and practically necessitating a measure of Japanese psyche to fully appreciate. But that’s certainly not to say that the manga lacks accessibility and charm. On the heels of the popular anime television series adaptation that simulcast worldwide earlier in 2016, One Peace Books offers English speaking readers the debut volume of the original 2013 manga series.

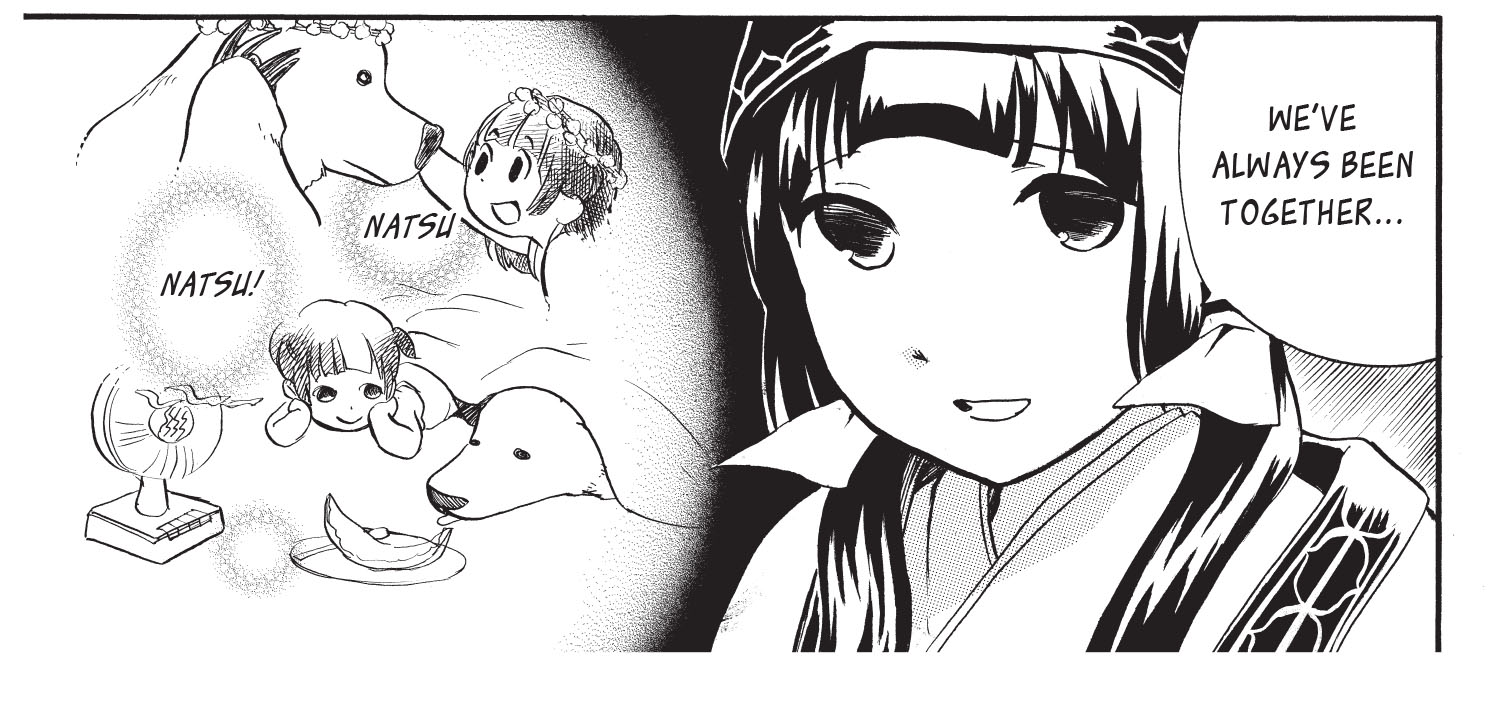

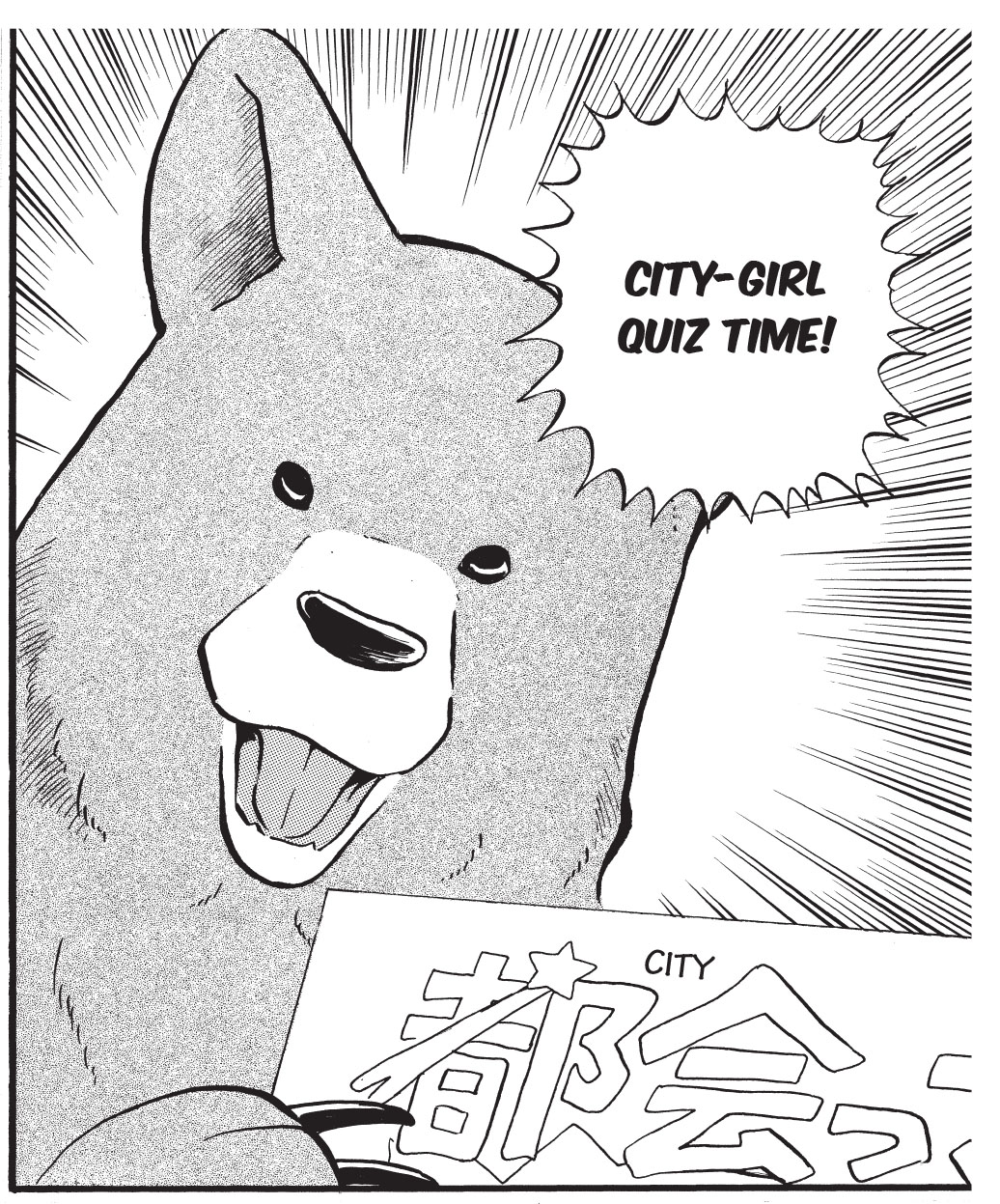

Kuma Miko, meaning “Bear priestess,” revolves around Machi Amayadori, a 14-year-old Shinto shrine maiden who lives in a rural mountain village in the Tohoku region at the northern tip of Japan’s main island. She’s kept company by her lifelong companion, the mild-mannered talking brown bear Natsu, who acts as Machi’s friend, parental figure, and connection to the natural spirit of the wooded land. Domestic conflict arises in the form of Machi’s insistent desire to attend school “in the city” and by extension see the larger metropolitan world that she’s never experienced. Natsu struggles to temper his desire to see Machi spread her wings with his awareness that she’s too timid, shy, and ignorant of urban culture to survive in the concrete jungle.

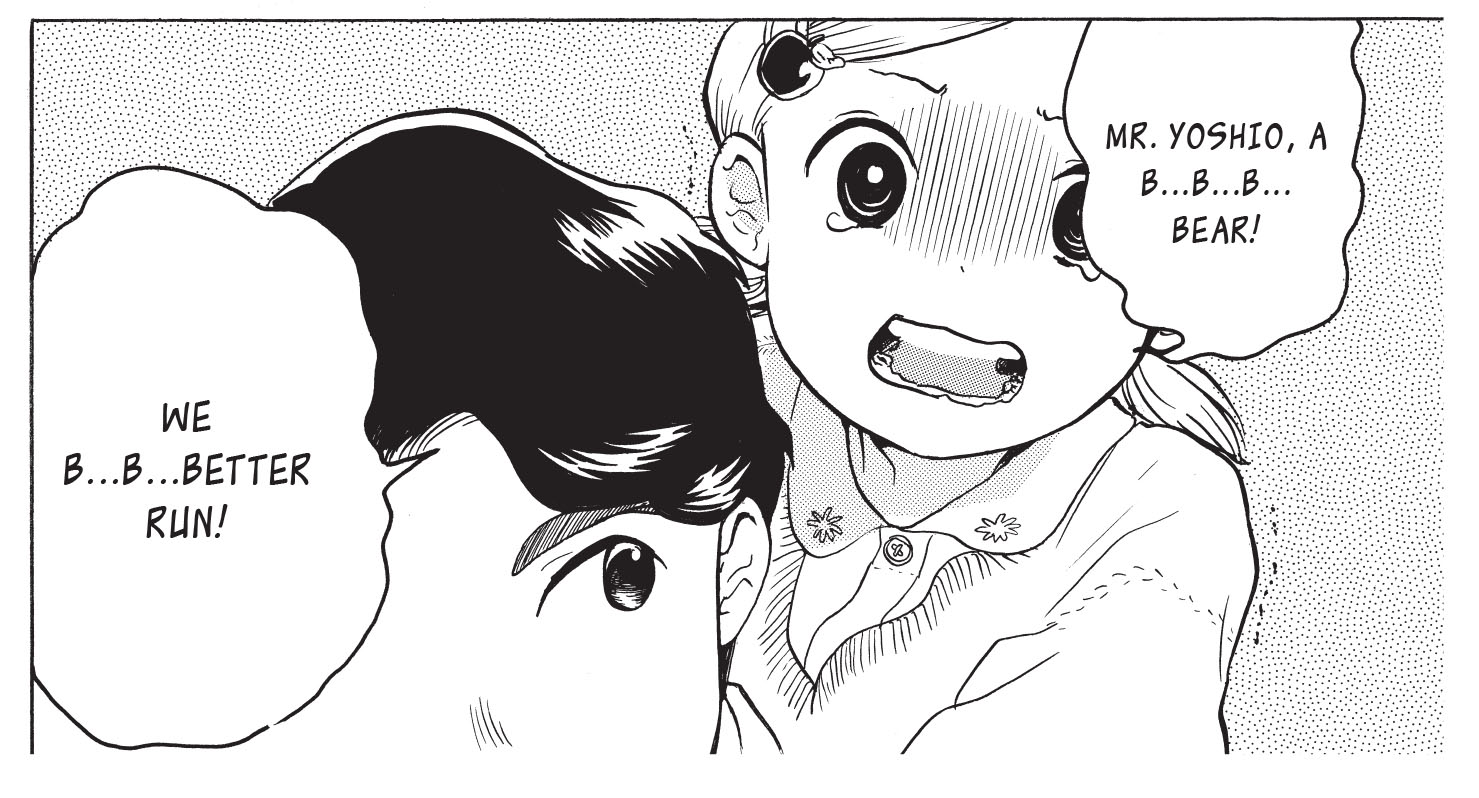

The slice-of-life Kuma Miko manga unfolds at a leisurely pace, gradually introducing its cast and taking care not to overplay its central conflict. The first volume contains six chapters and a bonus mini-chapter. The initial six chapters introduce Machi’s background and anxious curiosity about the outside world, her fretful excursion to a local department store, and the villagers’ clumsy effort to introduce some modernity into Machi’s life in the form of an updated summer ceremonial gown. The three-page bonus chapter gives readers a detailed proxy experience of cuddling a brown bear. The anime TV series adaptation was criticized for its bizarre hybrid of contrasting tones. The original manga is thankfully a bit more subtle and organic. The even monochrome color and the particular layout emphasis of Masume Yoshimoto’s art keep the reader’s attention consistently focused on the present and downplay the more slapstick and provocative elements of the storytelling. The story is a domestic comedy evoking a sort of family squabble between a well-intentioned parent and a rebellious teen child, so the story will be accessible to any reader. But distinct characteristics of the story are uniquely Japanese. So a reader’s understanding and appreciation of the gags may depend upon the reader’s innate understanding of Japanese culture. The sexually provocative origin of the village’s spiritual association with the local brown bears is present in the manga’s second chapter. The fable is communicated about as tactfully as the concept can be, revealing a degree of the cultural difference between the Japanese and Western acceptance of legends involving bestiality. (See Kyokutei Bakin’s ancient novel Nanso Satomi Hakkenden for another example of the literary permissiveness of cross-species sexuality in Japanese legends.) Furthermore, contemporary Japanese cultural references including Machi spiritually channeling Kyary Pamyu Pamyu and the prominence of Japanese idol culture pervading even isolated, rural, traditionalist Japan are instances in which the manga doesn’t alienate Occidental readers but may leave uninitiated readers scratching their heads, not understanding the jokes.

Kuma Miko is a manga that distinctly prioritizes its storytelling. The graphic art is functional but clearly intentioned to support and communicate the narrative. Yoshimoto’s art consists almost entirely of medium & close-up shots that give the manga a sense of intimacy but also a nearly claustrophobic feel. Background art is sparse and minimal, which is disappointing considering the lush, rich, and beautiful natural setting. Many panels lack any background art whatsoever. Because of the manga’s focus on close-up shots, a lot of the story is conveyed via facial expressions. The human characters are very expressive. However, early in the book Natsu is periodically drawn less like a bear and more like some sort of hook-nosed obese bird-monster. As Yoshimoto gets more experience drawing Natsu, his appearance becomes more consistent after the initial few chapters. Although Kuma Miko isn’t Masume Yoshimoto’s first manga, it is her professional debut publication, so it exhibits the characteristics of a talented but burgeoning manga creator.

One Peace Book’s 160-page first volume is presented entirely in monochrome. Japanese text is left intact and translated. Visual sound effects are left intact and translated when relevant. The English language translation is smooth, natural, and error-free save “loses” containing an extra “o” on page 147. Arguably distracting, select Japanese terms including “suica,” “kagura,” and “mugi-cha,” are Romanized rather than conventionally translated. In defense of the translation, Romanizing emphasizes the heavy Japanese-ness of this particular manga, and Japanese word puns are difficult to communicate via any translation choice. Particularly obtuse cultural references are noted and explained in a two-page glossary at the end of the book.

Readers anxious for a pulse-pounding, highly stylized manga aren’t likely to select Kuma Miko in the first place. Kuma Miko is an amusing slice-of-life character study set in rural Japan and steeped in the philosophy of slower-paced traditional Japanese life. Readers that are interested in conventional, typical manga may be bored by Kuma Miko. Readers interested in a manga that’s conscious of contemporary manga and J-pop trends yet focused on more insular and traditional Japanese culture will find Kuma Miko a bit uneven – a work at first unsteady and finding its legs – but rewarding specifically because it’s not so ordinary.