Entering The New Gate

While the modern day anime concept of a character being unwillingly transported to an alternate dimension or world, a story concept known as “isekai,” originated in the early 1980s, the “digital isekai,” a character trapped within an online role-playing game, debuted in anime form with 2012’s Sword Art Online. The initial Sword Art Online story proposed a scenario in which players who were logged into a digital simulation were unable to logout. Their digital lives became their real lives. This literary scenario exploded with such popularity that in less than a decade the setting has become a standard literary trope within the anime & manga. Being trapped in an MMORPG is now such an established fictional scenario that it no longer even needs explanation. That scenario sets the initial stage for author Shinogi Kazanami’s best selling 2013 light novel The New Gate and its manga adaptation by illustrator Yoshiyuki Miwa. New York based publisher One Peace Books will release the first English translated volume of The New Gate managa in print and digital formats on April 16.

The New Gate manga opens with protagonist Shin engaged in a climactic battle against the final boss of the online game The New Gate. When Shin defeats the ultimate gatekeeper, he heroically enables the game’s players to finally log-out and escape from the imprisoning ordeal. But heroic Shin himself, rather than leave the game last and turn out the lights behind him, is instead transported 500 years into the future of the New Gate world. His game winning champion status makes him exponentially stronger than seemingly any other being living in the fantasy world, but a half-century of cultural progression leaves him baffled and alienated. A brief plot summary of the first manga volume will likely conjure comparisons to other similar isekai stories including Death March to the Parallel World Rhapsody, Isekai Cheat Magician, Arifureta: From Commonplace to World’s Strongest, and Didn’t I Say to Make My Abilities Average in the Next Life?! but The New Gate isn’t without its own unique charm. Following the prologue that introduces the setting of the story, the first manga volume essentially occurs in only two locations: the medieval-style city Bayrelicht and the forest immediately outside its walls. Likewise, the cast is moderately substantial, but few characters stand out. Thankfully, the protagonist, Shin, is a level-headed and considerate fellow. He’s compassionate and easy-going by nature yet also rationally considerate of both himself and the people around him. So he’s not a very distinctive personage, but he’s easy to like and root for. The rest of the cast are strictly supporting characters given varying degrees of introduction. The elf women Tiera and Els and the human soldiers Beid and Aldi get just enough prominence to suggest that they’ll become more significant as the story proceeds. Characters Wilhelm Avis and Millie the orphan beast girl appear in little more than cameo introductions, yet both have enough personality to suggest that they may become fan favorite characters in future volumes. The 201-page first volume opens with a flashy epic duel which features some fairly explicit bloody violence. The remainder of the book depicts a friendly practice fight mid-way through and a bloodless monster duel in the sixth of seven chapters.

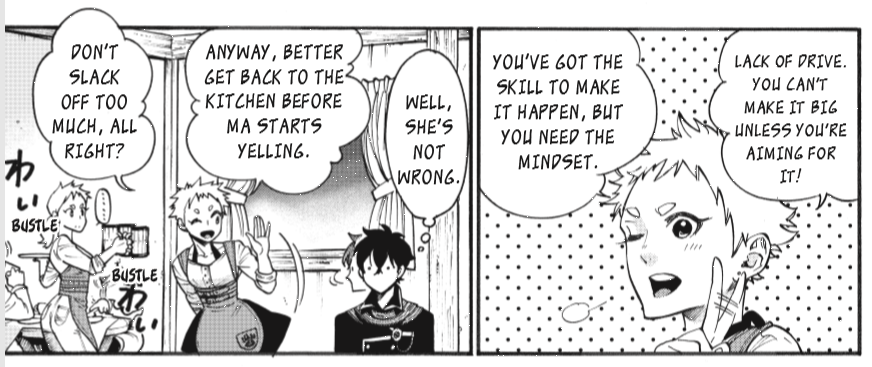

Yoshiyuki Miwa’s manga is largely very competent. Miwa’s illustration style features a medium level of detail that’s appreciable without becoming distracting. The few action scenes are mostly coherent although occasional panels lean toward confused abstraction. Since most of the first volume revolves around Shin finding his bearings in an unfamiliar world, the bulk of the book consists of character interactions and conversations. The character art typically feels modern while occasionally revealing influences that seem to include early 90’s seinen manga and Chinese wuxia comics. Background art is rather minimal and minimalistic, but Miwa skillfully selects and manipulates panel design and uses frequent medium and close-up views to disguise and minimize the need for detailed background art. Especially in the earliest chapters, screentone moiré is occasionally distractingly prominent, but that fault was present in even the original Japanese printing. Visual sound effects and in-panel text are retained unaltered with innocuous translations. The English language translation reads fluidly and error-free, especially doing a fine job of expressing varying characters’ personalities through nuances and inflections in their diction, formality, and accents. For instance, the haughty knights of the Bayrelicht Royal Order speak with a condescending formality, the seemingly seedy Alvis speaks with an almost snake-like sneer, and the bucolic guild master speaks with a disarming drawl. Apart from a few panels in the first chapter depicting a monster receiving bloody bodily harm, the 200 page manga contains no particularly offensive content: no sex or nudity, no harsh language, and very minimal graphic violence. The seven chapters contained in the book are entirely monochrome, identical to the original Japanese publication. The first book contains seven chapters, two pages of brief character introduction profiles, two pages of encyclopedic detail about the New Gate world’s systems of measurements and currency, and a single page afterword from the manga’s author.

Jaded and cynical manga readers are likely to dismiss The New Gate as “just another isekai” story. In the broadest possible perspective, the generalization is true, but the assertion is like lumping together and dismissing all action films that feature martial arts or all horror movies that include zombies. Similarity doesn’t automatically mean redundancy and unoriginality. The first manga volume of The New Gate is far more personable and approachable than the odious & distasteful premiers of comparable stories Rising of the Shield Hero and Arifureta. Moreover, occasionally, when opportunity allows, The New Gate demonstrates an amusing degree of metatextual recognition, poking fun at itself for adhering to genre conventions. But the first volume of The New Gate is especially conventional. The entire first manga adheres to the predictable formula of a new hero subsuming the extent of his abilities, registering himself with the local adventurers’ guild, securing lodging at the local inn, and undertaking his first low-level quest. Since The New Gate is deliberately composed as a derivation of the “digital isekai” trope, the series may initially be confusing to readers completely uninformed of the “isekai” subgenre. Readers who do enjoy the digital isekai genre will appreciate the first volume of The New Gate like a slice of pizza, overly familiar yet still tasty.

My review is based on an advance PDF provided by One Peace Books.